The Metaphor of Deepavali

Deepavali, or Diwali as commonly known, will be celebrated on the 12th of November this year. What is the inner, or spiritual, significance of Diwali in Sanatan Dharma? An excerpt from Partho's latest book.

The Mystical Core of Hindu Dharma

The Mystery of the Self

We are now ready to delve deeper into the mysteries of Hindu dharma. Once the Veda secret in the heart has awakened and leads forth the disciple, the path becomes safer and quicker, for the Veda in the heart is an infallible guide, it is the voice of the Divine seated in our hearts as the inner guide and Guru.

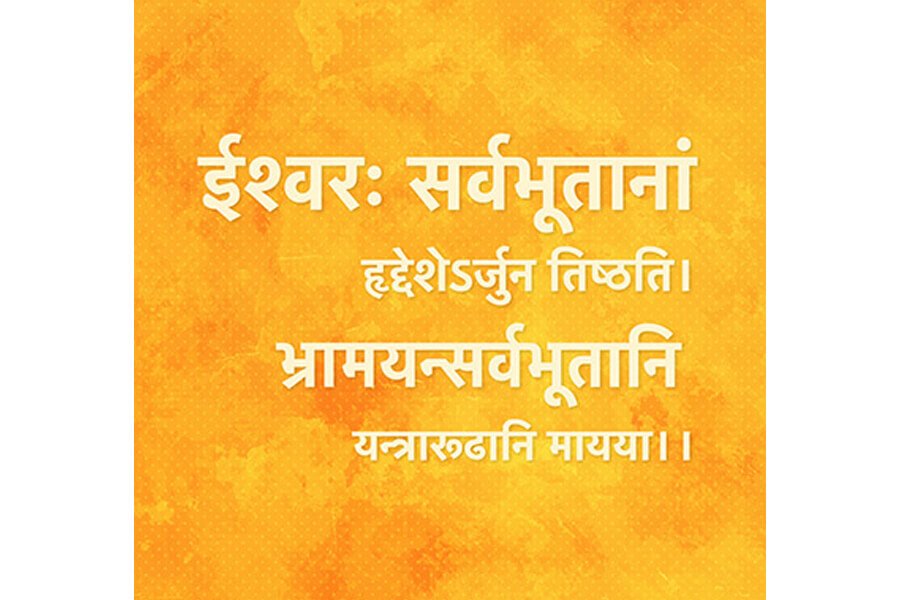

In the Bhagavad Gita, perhaps the most lucid and comprehensive of all shastras of Hindu Dharma, Sri Krishna, the Divine Teacher, says to Arjuna, the disciple — Ishvarah sarva bhutanam hriddeshe’rjuna tishthati [1] — O, Arjuna: the Divine is seated in the heart of all living beings. This one simple statement is the master key to the myriad mysteries of Hindu Dharma.

Ishvara, as the Divine Teacher and Guide, is seated in the heart of every living being — this is a mahavakya : a statement of profound and seminal importance which can have the effect of potent mantra if taken to heart and followed through to its natural conclusion (more on mahavakya a little later). One who can base his whole consciousness on this single truth will need no other teaching or teacher, for the Divine in the heart will become for him the source of unfailing and unwavering trust, faith and motivation. Knowing that the Divine is in one’s own inmost self, where else would one need to go? Grasping this one thread, the seeker can walk through all possible psychological and metaphysical mazes unerringly on his way to the realization of the Self or God.

The first step on the path to realization is to turn one’s attention inward from the external world and its objects and plunge within, into one’s inmost being, the heart or the hridaye, and there find the presence of Ishvara as one’s own most intimate self, the atman.

When Sri Krishna declares that Ishvara is seated in the heart of all living beings, he is referring not to the physical heart, nor even to the heart centre in the body, but to the heart which is symbolic of the centre of one’s consciousness — the hridaye guhayam or the cave of the heart in Hindu Vedic mysticism; this cave of the heart is the centre of one’s consciousness. The inner plunge of the mystic is the act of withdrawing one’s attention from the objects and subjects of the world and concentrating it on the centre of one’s consciousness. This is the first practice of dhyana in mystical Hinduism.

The cave of the heart, hridaye guhayam, the secret centre of one’s consciousness, is the altar of the Divine, this is where Ishvara is seated as one’s own inmost being, the self or the atman. The discovery of the atman, the inmost Divine, is the first indispensable spiritual realization of Hindu dharma; one may safely say that the true pilgrimage of sanatan Hindu dharma begins only with this all-consuming discovery of Ishvara as one’s most intimate self.

As one approaches the atman, one begins to receive the first glimpses of the supreme mystery of the Divine, one begins to experience Ishvara not only as the centre of one’s own consciousness but the selfsame centre of all consciousnesses in all forms. This is a mula anubhava, essential realization, of the seeker of sanatan dharma, that the same Ishvara resides in all living beings as atman, and the atman is the same everywhere.

The rigid boundaries of one’s egoistic consciousness then begin to melt, and for the first time, one begins to experience oneness in all creation; the world is no longer experienced in terms of differences and contradictions but increasingly in terms of one unbroken existence, everything and everyone made of the same spiritual substance and possessing the same psychic essence. This new way of seeing and relating to the universe arises from anubhava, inner experience, and can therefore be tremendously powerful and transformative.

It is on the basis of such spiritual realizations of oneness that Hindu dharma declares the truth of human unity in such trenchant syllables — vasudhaiva kutumbakam : the whole world is but one single family. [2]

The experience of the atman is a fundamental movement in one's progress towards the realization of the Divine. The realization of atman, the Divine in the heart, becomes the practical basis for the higher realizations of Hindu dharma. For once the Divine is known in the centre of one’s consciousness, the Divine in revealed in all objects and beings — as if the whole universe becomes divine, and all sense of division, isolation and fear falls away permanently from the consciousness of the seeker. The seeker then becomes a devotee, and all mental seeking and knowledge are swiftly replaced by spiritual wisdom or prajna.

Prajna (a term used to denote higher or deeper wisdom in both Hindu and Buddhist psychology) is the opening of a higher order, supra-intellectual faculty which grasps truth intuitively, without having to work its way through processing of information and logical reasoning. The Dharma, at this point, transcends the reasoning buddhi in its ascent towards the supreme Truth and finds for itself a higher vehicle and expression in the prajna.

Through the higher workings of prajna, the devotee now comes to the threshold of the next fundamental realization of the Sanatan Dharma: that the atman is indeed Ishvara, the Divine, and in finding the atman, one finds Ishvara.

The Divine in Hindu Dharma

What is the nature and attributes of Ishvara, God or the Divine in Hindu darshan and dharma? The first Upanishadic pronouncement on the nature of the Supreme God of Hinduism is that the Supreme God — param Ishvara — is unknowable by mind and indescribable by human thought or speech, it is anirvacniya, that which cannot be thought or spoken of. Param Ishvara is Truth itself, Sat, and can only be known by becoming one in consciousness with Sat, what the sages call knowledge through identity. The human seeker or devotee can indeed identify with that param Ishvara only because that param Ishvara already dwells in the consciousness of living beings.

Having stated that Ishvara can only be known inwardly through identification in consciousness, the Upanishadic seers then attempt to describe Ishvara through a series of mahavakyas, defining pronouncements or maxims of Hindu darshan (literally, maha, great; vakya, pronouncement or statement). These mahavakyas are aphoristic pronouncements with profound mantric power — if rightly analyzed, meditated upon and assimilated, each of these mahavakyas can take the disciple to the essential truths and realizations of the deeper Hindu Dharma.

Ishvara is seated in the heart of all living beings is one such mahavakya which opens the gateway to the profoundest mysteries of the Dharma. Having realized the truth of the mahavakya in one’s inner experience, the devotee moves on to the realization that not only is Ishvara seated in the heart as one’s atman, as Supreme Brahman, It (He or She in a more personal sense) pervades and fills the whole manifested universe. Not only this, the deeper truth is even more compelling — that this manifested universe with all its infinite variations of form is nothing but Brahman.

Sarvam khalvidam brahma, this Upanishadic mahavakya, takes us right to the heart of the Dharma. From the Chandogya Upanishad, sarvam khalvidam brahman literally means that all this — all that is manifest and unmanifest, all that is known, not-known and not-knowable — is equally Brahman, the Divine.

Gleaned from across the span of the Upanishads, one can attempt at least a working approximation of Brahman: Brahman (from the root brh, expand) is unlimited, without dimension or boundary, infinite and eternal: akshayam, sarvam,anantam, nityam. Brahman, as the all-transcendent, parabrahman, is beyond all manifestation, and as atman and Ishvara, is immanent in all manifestation.

That which the human mind cannot know, nor the senses apprehend, is Brahman, jnanatita, sarva-indriyatita ; Brahman is that which cannot be described in any human language, cannot be brought into thought or speech, anirvacniya. Brahman as the Supreme Self, purushottama, is the Knower of all that is and can be known, the Seer of all that is and can be seen; the consciousness of all that is conscious and can be made conscious. Brahman, as param Ishvara, is the Supreme Godhead, the source and end of all that is, was and ever shall be; the all-pervasive, sarvavyapi, that which saturates the Universe, sarvam brahmamayam jagat; that which is the substratum of all being and becoming, mula adhara, the background of all experience, is Brahman; Brahman is the very fabric of space and time; the all-Perfect, purnam, the perfect peace and knowledge: shantam, jnanam.

Not only does Brahman pervade all as the Vast, the brihat, it even penetrates into the minuscule, the subtlest — into the smallest particle of matter and pulsation of energy, into the very cells and nuclei of life, even into the subtlest movements of consciousness, right down to our subtlest thoughts and intentions, all is pervaded and informed by Brahman. If Brahman were to withdraw, even for the most infinitesimal fraction of a second, all this that we know as the manifest universe would simply vanish into nothingness.

But even after having attempted such a description of Brahman in such superlatives, it still eludes human understanding, remains unexplained and unknowable, for if Brahman is all there is, if there’s none or nothing outside of Brahman, then who is there to know Brahman? Brahman, being the all-consciousness and all-existence, is the only Knower, so how shall the Knower be known?

Several Hindu sages have declared this point as the final cul-de-sac: none can go further with the existing mental machinery and the weight of mental knowledge. All knowledge, all thinking and reasoning must now be abandoned. This is the culmination of the Vedas as we know it — vedanta.

Vedantic Hinduism

Tat twam asi

Even before we can fully comprehend this stupendous idea of Brahman, the all-pervading Infinite Consciousness surrounding, possessing and filling us like some invisible ocean, we come to another equally awesome idea that this Infinite Sea of Consciousness, this Brahman, is what we, in our essence, actually are. Tat twam asi — a resounding Upanishadic mahavakya states unequivocally that the human ( twam, you), in her inmost atmic truth of being, is Brahman, the Divine ( tat, That; asi, are).

At first, most would baulk at such a pronouncement: for who amongst us can hold the thought of being Brahman for even a few seconds without the mind crashing? The human mind pushes outward, the truths it seeks are always outside, somewhere high up in some remote heaven. Men can have faith easily in a remote God in the high heavens but to believe (and live) the truth that one is God oneself in one’s inmost depths is somehow too farfetched. Yet, this is the profound truth of Hindu dharma: that the Vast and Infinite Brahman is the same atman within the cave of the heart. This atman, says another profound Upanishadic mahavakya, is that Brahman: ayam atma brahman.

But to know oneself as Brahman one must first enter those sublime depths of being where the atman shines through in all its radiance, one must leave behind all the dross of the human world, all its din and tumult, and learn to live, more and more, in a silence unbroken even by thought.

In that silence, that inner chamber of the temple to Brahman, one experiences the inner alchemy as one’s knowledge of the mind, jnana, ripens into sraddha, the creative force of faith that can bring into reality whatever one holds in one’s mind and heart with sincerity and unwavering perseverance; sraddha is a psychic force for realization, and with sraddha, all things become possible.

Sri Krishna explains sraddha to Arjuna in these words: The faith of each man takes the shape given to it by his stuff of being, O Bharata. This Purusha, this soul in man, is, as it were, made of sraddha, a faith, a will to be a belief in itself and existence, and whatever is that will, faith or constituting belief in him, he is that and that is he. [3]

Sraddha then is the creative force that transforms knowledge into faith, devotion and surrender to that which one seeks to become. The completion or purnata of Hindu dharma happens naturally when jnana or knowledge (the mind's knowing) transforms through sraddha into bhakti, love and devotion, and flows out spontaneously into karma, action as inner sacrifice to the Divine. These three, jnana, bhakti and karma, are the three pillars of Sanatan Hindu dharma. Through these three streams, the devotee realizes her identity with the Supreme Being, Brahman as Purushottama.

Anubhava, the Unfolding of the Experience

In small measures, in ever so subtle and simple ways, the devotee realizes that there is no object of knowledge out there, there is only the Knower and the knowing; and there too, there is no duality, for the knowing is only Self-knowing. She begins to understand, ever more practically, that the world or universe she believed to be outside of herself is not outside at all: it is all one's own reflection. There is no outside or inside : there are only reflections. The so-called world “out there” is a mirror of consciousness, and all one sees and experiences there is Self. In a more fundamental sense, the so-called objective world is only a mode of Self-knowing.

The devotee then truly begins to see, his vision passes beyond the gross into the subtle reality of things and beings, and he develops a new way of seeing, what our seers called sukshma drishti, the subtle vision. It’s not that the world becomes subtle, the world remans what it is; it is one's perception that begins to discern the subtle in the gross, the spirit in matter, the true in the mithya.

This subtle perception, sukshma drishti , sees beyond the appearance of multiplicity and sees the One Self everywhere, in all, from oneself spreading outward through all of the known universe. The best description of this perception comes, perhaps, from Sri Ramakrishna who once said, do you know what I see now? I see that it is God Himself who has become all this. It seems to me that men and other beings are made of leather, and that it is He Himself who, dwelling inside these leather cases, moves the hands, the feet, the heads. I had a similar vision once before when I saw houses, gardens, roads, men, cattle — all made of One substance; it was as if they were all made of wax.

This subtle seeing begins of course with oneself: It is one’s own personal self that is the first veil or mask to fall away and reveal the true Face. It is only when we see our own personal form as a veil at once concealing and revealing the Self, regard our very act of perception as the conscious gaze of the Self seeing through “our” physical senses and knowing through our minds, that we begin to see through all outer faces and façades, and glimpse the one same Self gazing outward through all physical forms and embodiments.

It is like seeing in a different light: the face of the other becomes transparent and we begin to see the Self behind the face, and not really “behind” in a physical sense but we see the outer physical face as a mere superimposition on the true Face which is more of a countenance, an expression, and not a physical shape at all. The outer physical face, the form or rupa, is still there but the True Face is so clear in the background that we no longer pay attention to the outer face. The outer face is a façade, a mask, which becomes increasingly transparent to the growing inner vision of the One in all forms. This is what Hindu darshan calls the advaita bhava, the sense of non-duality in multiplicity. It is this bhava that is the practical basis for living the Hindu dharma.

When the Hindu therefore says ahimsa paramo dharma, non-violence is the supreme dharma, he does not mean it as a moral injunction or an intellectual idea: he means it practically and concretely: since he sees the one Divine in all forms, how can he not be non-violent? The Hindu does not seek to propagate non-violence as an ideal: he seeks to eliminate the last tendency of violence, from the grossest, the most physical to the subtlest psychological, from all parts of his being; in other words, he seeks to embody ahimsa. Likewise, when he speaks of truthfulness and sincerity, it is not from the moralistic or intellectual standpoint at all; in these too he seeks to embody truth not because he has an intellectual conception of it but because he lives it in anubhava: these are facts of integral experience to be lived.

Thus, to know Brahman as this universe, in all its details, and to know the self as Brahman, and to know all other forms as the same Brahman, is the threefold dharma of the Hindu. This is the dharma that was given the name Sanatan by the ancient seers and sages. This Sanatan Dharma, known today as Hindu dharma or Hinduism, is the actualization of the Divine in humanity’s mind, life and body. The Sanatan Dharma knows no outsider, no alien; none can be permanently hostile to the Dharma for in all, even in that which appears antithetical to Dharma, adharmik, there dwells the same Divine, the same Truth. Therefore the Hindu, standing firm on the realizations of Sanatan Dharma, can say that Truth or Dharma will finally prevail — satyameva jayate.

Those who choose to walk the path of the Dharma, not merely profess to be religious, those who can free themselves of the gravitational pull of their egoistic consciousnesses and give themselves in mind, heart and body to the demands of the Dharma, those who can walk boldly the Upanishadic path, ascending peak upon peak of human consciousness in their relentless quest for Truth, Light, Bliss are the ones who will emerge victorious in this timeless battle of Dharma against the forces of adharma. These indeed are the children of Immortality, amritasya putra, who alone have the spiritual right to carry forth the Sanatan Dharma from age to age.

1 ईश्वरः सर्वभूतानां हृद्देशेऽर्जुन तिष्ठति। भ्रामयन्सर्वभूतानि यन्त्रारूढानि मायया।।— Bhagavad Gita, 18.61 ↑

2 From the Maha Upanishad — अयं बन्धुरयंनेति गणना लघुचेतसाम् / उदारचरितानां तु वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम् — The distinction this person is mine, and this one is not is made only by those who live in Ignorance and duality. For those of ‘noble conduct’, who have realized the Supreme Truth and have transcended the multiplicity of the world, the whole world is one family. ↑

3 सत्त्वानुरूपा सर्वस्य श्रद्धा भवति भारत। श्रद्धामयोऽयं पुरुषो यो यच्छ्रद्धः स एव सः।। Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 17, Verse 3. The rendering of this verse in English quoted above is Sri Aurobindo’s. ↑

A practitioner and teacher of Vedanta who prefers to write and speak anonymously. A teacher, in the dharmic tradition, is known as 'Acharya'.

Deepavali, or Diwali as commonly known, will be celebrated on the 12th of November this year. What is the inner, or spiritual, significance of Diwali in Sanatan Dharma? An excerpt from Partho's latest book.

The first of a four part series on Vedanta from Swami Vivekananda’s famous ‘Calcutta address on Vedanta’ delivered in Calcutta on January 19, 1897. This talk marks a significant moment in Swamiji’s life and is considered one of his most important speeches on Vedanta, where he explains some significant aspects of Sanatan Dharma

A series of conversations on Sanatan Dharma and Vedanta between our editors, Dr Singh and Partho. This is the first conversation in the series, describing the initial process of Vedanta