The Metaphor of Deepavali

Deepavali, or Diwali as commonly known, will be celebrated on the 12th of November this year. What is the inner, or spiritual, significance of Diwali in Sanatan Dharma? An excerpt from Partho's latest book.

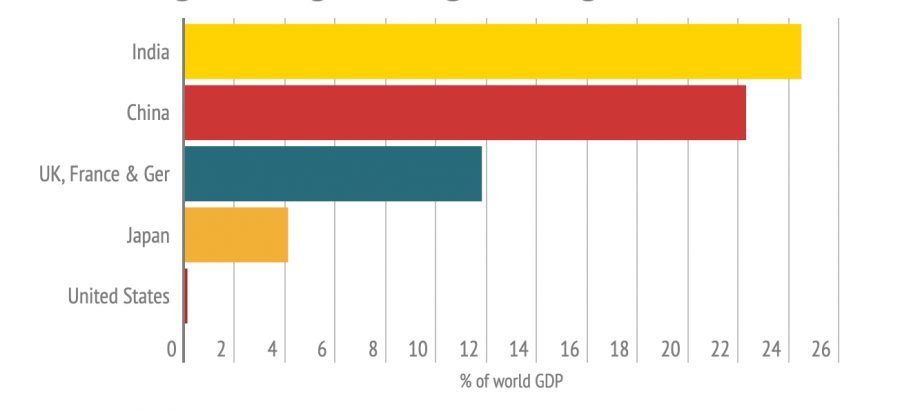

Between 1-1700 AD, India was consistently one of the largest contributors to the world economy, her contribution ranging between 32% and 25%. It is during this period that India was known widely as “Sone ki Chidiya”, the Golden Bird. China was almost similar to India in her contribution. These were pre-industrial revolution days. Both regions had advanced ancient civilizations, highly developed in all aspects. Life was lived in harmony with nature in those times.

Share of world GDP – 1700 AD [1]

For many centuries India was like a Jagat Guru or a World Teacher. We had great philosophers, seers and spiritual scientists (Rishis and Yogins). We possessed great sciences of the mind and soul, some of the oldest and most advanced philosophies (notably the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita), a highly evolved science of health, longevity and well being (Ayurveda, Siddha, Hatha Yoga, Pranayama and meditation), and a highly sophisticated ecosystem of languages, based on Sanskrit, a language that has been called the mother of all languages. We had a vast body of literature and poetry in Sanskrit and local languages. There exist a large number of texts in Sanskrit and local languages that document the extent and scope of Indian knowledge.

Apart from all these, there are several other domains of knowledge that were present in India which included architecture and town planning, physical and social sciences, astronomy and mathematics. Most of these domains and branches of knowledge continue to be practiced and taught in some form even today.

In the words of Sri Aurobindo:

When we look at the past of India, what strikes us is her stupendous vitality, her inexhaustible power of life and joy of life, her almost unimaginably prolific creativeness. For three thousand years at least,—it is indeed much longer,—she has been creating abundantly and incessantly, lavishly, with an inexhaustible many-sidedness, republics and kingdoms and empires, philosophies and cosmogonies and sciences and creeds and arts and poems and all kinds of monuments, palaces and temples and public works, communities and societies and religious orders, laws and codes and rituals, physical sciences, psychic sciences, systems of Yoga, systems of politics and administration, arts spiritual, arts worldly, trades, industries, fine crafts,—the list is endless and in each item there is almost a plethora of activity.

There is no historical parallel for such an intellectual labour and activity before the invention of printing and the facilities of modern science; yet all that mass of research and production and curiosity of detail was accomplished without these facilities and with no better record than the memory and for an aid the perishable palm-leaf. Nor was all this colossal literature confined to philosophy and theology, religion and Yoga, logic and rhetoric and grammar and linguistics, poetry and drama, medicine and astronomy and the sciences; it embraced all life, politics and society, all the arts from painting to dancing, all the sixty-four accomplishments, everything then known that could be useful to life or interesting to the mind, even, for instance, to such practical side minutiae as the breeding and training of horses and elephants, each of which had its Shastra and its art, its apparatus of technical terms, its copious literature. In each subject from the largest and most momentous to the smallest and most trivial there was expended the same all-embracing, opulent, minute and thorough intellectuality.

(The Renaissance in India – I, Foundations of Indian Culture)

Most of this knowledge was given and gained through a highly evolved education system known as the Gurukul. Gurukuls were the traditional custodians of secular and spiritual knowledge. In the traditional Gurukul, new knowledge was developed by constant inquiry and experimentation and the knowledge was shared with students (shishyas) who would take it to society and look after its development for the future. All existing knowledge was organized, documented and preserved for anyone to access, anytime in the present or the future. Outdated knowledge was updated or discarded. This tradition and system of generating and applying knowledge across various aspects of human and social life was already in decline when the Mughals arrived, followed by the British. Even up to the end of the Mughal period, India continued to be a country of immense prosperity with the highest advanced knowledge traditions and a largely stable society.

However, as always happens with civilizations everywhere, a great period of prosperity and efflorescence is always followed by decline and degeneration. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries indeed marked the beginning of such a decline.

…Undoubtedly there was a period, a brief but very disastrous period of the dwindling of that great fire of life, even a moment of incipient disintegration, marked politically by the anarchy which gave European adventure its chance, inwardly by an increasing torpor of the creative spirit in religion and art,—science and philosophy and intellectual knowledge had long been dead or petrified into a mere scholastic Punditism,—all pointing to a nadir of setting energy, the evening-time from which according to the Indian idea of the cycles a new age has to start. It was that moment and the pressure of a superimposed European culture which followed it that made the reawakening necessary.

(The Renaissance in India – I , Foundations of Indian Culture)

Soon after the Industrial revolution, India passed under British rule. The British, as the rulers, brought in with them their own culture and civilization which they imposed on the peoples of India. This led to a rapid and continuous decline of the original Indian culture and civilization. The same trend, unfortunately, continued even after Independence as a large majority of Indians unquestioningly accepted the ways of the western world as their new values and ideals.

The western industrial civilization, which has exclusively dominated the world during the last two centuries, has led to imbalance in the world which has not been good for anyone. With an excess of industrialization, we have had excessive use of synthetic chemicals, a serious depletion of nature and natural resources, widespread competitiveness amongst all strata of people, and a consequent loss of compassion, peace and wellbeing.

The Indian opportunity

These very challenges and problems that have come in the wake of westernization and globalization can also become a great opportunity for us. These critical issues of modern global society can be looked at anew from an original Indian point of view and creative solutions found.

For this, we will need to go back into the depths of relevant traditional practices and knowledge systems of ancient India, understand them deeply, and out of that knowledge, create products and services for our contemporary needs and make them available to a global society. The process of creating these solutions and products should not proceed by rejecting modern knowledge and practices but incorporating the best of those practices and knowledge systems.

The natural tendency of the Indian mind is to synthesize, not to divide. Hence, we should openly embrace the advancements of modern society, science and technology. What we need to avoid are the vital-egoistic tendencies of division, competition, exclusive self-interest, destruction of nature, excess of consumerism and other similar extremes.

That was in fact what our own ancestors did, never losing their originality, never effacing their uniqueness, because always vigorously creating from within, with whatever knowledge or artistic suggestion from outside they thought worthy of acceptance or capable of an Indian treatment.

(Indian Culture and External Influence, Foundations of Indian Culture)

With an open mind and heart we should synthesize and harmonize the original Indian knowledge with advances in the modern world, across domains of knowledge, science and technology, and especially the information and computing technologies.

With this as a basis, we should create solutions that are rooted in the essential Indian principles and worldview. Which means that all our products and methods will truly be sustainable and in harmony with nature as well as human society, a conscious adoption of these will automatically lead to a much more balanced world. This is a great economic opportunity and will lead to the creation of “good” wealth and long-term prosperity for India and her people — this can become a big part of our Aatmanirbhar Bharat mission. A large global population is waiting to adopt our products and services.

There are two main stakeholders needed for this movement to happen. First would be the entrepreneurs —those who will start projects that would identify the important problems, do the R&D on finding and building solutions and finally bring them to the market in the form of products and services. The second important stakeholder would be the government, both at the center and state — the government can play the role of a constructive partner by creating policies, supporting frameworks and a generally facilitative environment.

An ecosystem of entrepreneurs:

A National Policy

The central government should come up with a national policy which makes a sincere attempt to contribute towards these initiatives. Such businesses will create wealth of the best kind, which is generated by bringing balance to earth and goodness to humanity. The policy initiatives can be along the following lines:

The civilizational consciousness of India has been growing quite vigorously in recent years and as a result, an economic renaissance based on the Indianness is almost inevitable. What exact shape and structure will that take remains to be seen.

A student of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, deeply interested in Indian Spirituality and its relevance to the present and future of humanity, also a Co-founder of Supermorpheus, a community based ecosystem for building conscious startups.

Deepavali, or Diwali as commonly known, will be celebrated on the 12th of November this year. What is the inner, or spiritual, significance of Diwali in Sanatan Dharma? An excerpt from Partho's latest book.

आज की तत्काल आवश्यकता है की आध्यात्मिक एवं बौधिक स्तर पर विकसित लोग सनातन धर्म के लिए खड़े हो, उसकी रक्षा करें और उसके प्रवक्ता और वार्ताकार बनें।

The Age of Sri Aurobindo is here...Excerpted from a talk on Sri Aurobindo and His Relevance in Present-Day India delivered by Dr. Pariksith Singh recently in Jaipur.